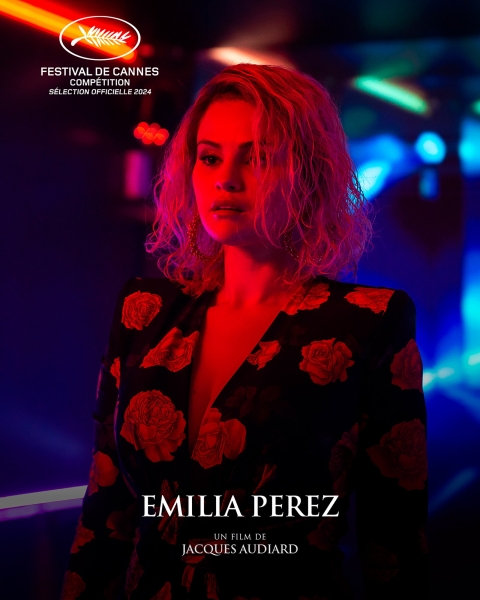

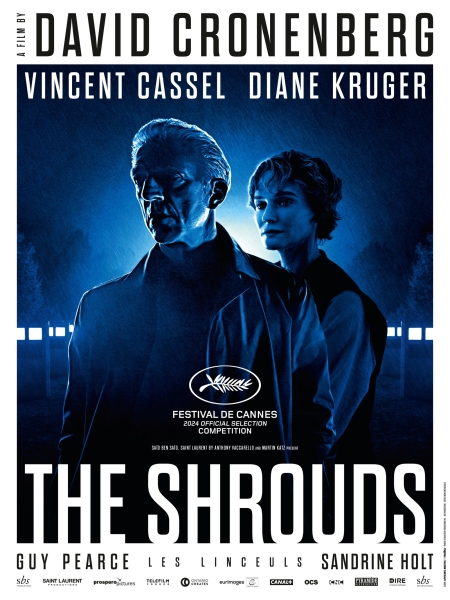

Saint Laurent’s Anthony Vaccarello will have a very busy time at the Cannes Film Festival this year. Saint Laurent Productions, a relatively new division set up by the house to produce the films of iconic auteur filmmakers—their first offering, in 2023, was Pedro Almodóvar’s Strange Way of Life—will premiere three this year at the festival: David Cronenberg’s The Shrouds, Paolo Sorrentino’s Parthenope, and, from Jacques Audiard, Emilia Perez, starring Selena Gomez, Zoe Saldaña, and Edgar Ramirez, among others. (With a lineup of directors like that, thank goodness we have the phrase embarrassment of riches to fall back on.)

What follows is a conversation with Vaccarello in the lead-up to Cannes. And what emerged from our chat is that while Vaccarello is a cinephile, he also astutely realized that the best way for a venerable fashion name to make a creative difference in today’s world—while simultaneously allying two of France’s great cultural obsessions, fashion and film—was to offer the kind of financial support that would allow directors to make the kind of movies they really want to make.

Saint Laurent has costumed all three movies, but you won’t see any kind of commercial play—whether via product placement or with the costuming spun off into capsule collections and the like. Vaccarello is an astute designer who understands that oftentimes creativity and commerciality have to be joined hand in hand—yet with this passion project, he believes they can also sometimes just admire each other from afar.

Vogue: Before we chat about Saint Laurent Productions, Anthony, I’d love to ask you about your earliest memories of films and directors you loved, and why you were into them.

Anthony Vaccarello: Film has always been something I was really, really into—I was born in Belgium, not the most exciting country in the world [laughs], and so film was a good field to explore to see something that wasn’t my real life… to escape a bit and to dream. At the beaux arts school that I did before La Cambre [the renowned fashion school in Brussels], I saw the work of realisateurs [directors] like [Pier Paolo] Pasolini and [Rainer Werner] Fassbinder, and I wanted to see more and more, go deeper into what they did. I wasn’t a fan of everything they did, but their films that were strange were my thing.

It’s interesting you say Fassbinder and Pasolini, because the work of both directors is visually beautiful, in very different ways—well, maybe beautiful isn’t the right word; perhaps striking.

It’s a kind of beautiful: a dirty beautiful.

Yes, exactly. Which of their films did you particularly like?

From Pasolini, Salò [Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom] to Teorema [Theorem]…. Salò was a big shock for me.

I’ve never been able to work up the courage to watch it. I know it’s not exactly a comfortable viewing experience.

It’s strong—and it is related to what is happening today, I think. And from Fassbinder, I mean: all of them. From Querelle to The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant….

Yeah, Petra von Kant is amazing: The character is a fashion designer, right?

Yeah, I love that.

I’ve always thought it was a bit of a cliché to assume that designers are inspired by films—you know, “Oh, I was looking at the costumes in such-and-such for this collection”—but I’d love to know if film factors into your thinking as a designer at all. Maybe the sense of escapism, or the notion of a certain character? When I look at your collections, I always see and feel a character far more so than a series of visual inspirations.

When I look at films I love, I am not thinking of the look, or of specific clothes—take Belle de Jour, for example: The appeal is always more the character blending into the story that makes a film something you remember. Was that the question, or no?

Kind of a question [laughs]—I guess I’m interested, given that you have launched Saint Laurent Productions, if film sparks any of your creative processes in any way….

Saint Laurent was always such a cinematic house, but I thought it could be good for the house to be linked directly to film production, rather than just doing costuming, which is more expected.

Saint Laurent himself did movie costumes, what with Belle de Jour….

Belle de Jour, and La Chamade, which also starred Catherine Deneuve—and Saint Laurent also costumed for the theater, which isn’t my thing. But he never produced films.

I know you’ve become good friends with Catherine Deneuve. Have you talked with her about getting into the film world?

Yeah—she was like, “It’s brave, and it’s a good thing for cinema.” I know some French producers are a bit cold about the idea of a fashion house producing films, but they’re just not used to it—I think it’s good that we have new producers coming into the business. It’s cool to change the rules.

Talk to me a little about setting up Saint Laurent Productions.

When I started at Saint Laurent I always wanted to see my collection captured by a master, in much the same way Saint Laurent’s collections were photographed by Helmut Newton. Early on, I would collaborate on these little films about the collections with Wong Kar-wai or Brett Easton Ellis; I always wanted to have the best realisateurs to link to the name of Saint Laurent. So it started slowly like that: a little clip of a film lasting four, five minutes.

Then I met Gaspar Noé, and we became very close. We started with a little movie clip, and then we did our first short film [Lux Aeterna, or Self 04, which starred, among others, Béatrice Dalle and Charlotte Gainsbourg], which went to Cannes [in 2019]. When I think about my career at Saint Laurent, it’s one of my best memories, because it was selected to be shown at 10 at night—and when I was a kid I always watched the Cannes festival with my mom, and those things that were shown at 10, or at midnight, were always the movies I was interested in: the controversial ones, like David Cronenberg’s Crash.

Being there with Gaspar and Béatrice was an important moment. I began to think about working with filmmakers I admired when I was younger, and we started with Pedro [Almodóvar], who was for me like my godfather. It went super well, and we thought, Okay—let’s continue to make that dream come true.

Could you talk a little more about the impulse to work with specific directors?

From the beginning, it was about helping filmmakers make their films, because it’s harder and harder these days for cinema to get the budget to do what they want without suffocating the production so that they have to change their vision. My role [at Saint Laurent Productions] is to choose which filmmaker.

[When we work together] they share what they want to do, and the scripts; we talk about the cast. We build it like that. I have so much respect for what they do, and I feel it wouldn’t be relevant for me to say, “You’re wrong.” The directors we work with are masters in their field.

For us at Saint Laurent, it gives us new ways to communicate. In doing those films, the name of Saint Laurent stays forever. When the name is on a billboard, it’s so fast—one month later, we forgot about it—but in 20 years the name Saint Laurent is still there.

Saint Laurent himself was a kind of fashion auteur: Who he was, and his vision, are so evident in his designs, in much the same way that we think of the creative output of a [Jacques] Audiard, or a Cronenberg, or a [Jim] Jarmusch. I think fashion and film are also similar in that they both have creative and commercial aspects, with different designers or directors prioritizing one or the other. With your last collection, I remember you telling me backstage that not everything needs to be driven by commerciality.

It’s good to sometimes show [a collection] and to be able to be free to talk about art and beauty—that not everything is based on money and profitability.

You mentioned you were a long-term fan of Almodóvar’s. What was it like meeting him for the first time?

We met at the Sunset Marquis [in Los Angeles]. I was very stressed, because sometimes you think Spanish people, like Italian people—I am Italian—are going to be very warm, and they’re not [laughs]. His films are hysterical and colorful, and he was the opposite of that, but at the same time, he was who you would expect Pedro Almodóvar to be. I don’t quite know how to put it, but if you love his films, you love Pedro Almodóvar.

Are you checking in with the directors whose movies you’re producing—texting or calling them to ask how it’s going?

It depends on the relationship—with Pedro or Jim, yes.

I’d like to ask you about the costuming of the Almodóvar movie. What was that process like?

It was interesting—we are so used to seeing Westerns in black and white, but when Pedro found color stills of Last Train from Gun Hill, the film he was inspired by, the colors were actually very strong. There was one scene with Pedro Pascal where [Almodóvar] wanted a bright green jacket, and I was like, It’s a bit strange, but okay: It’s Almodóvar.

He was very specific about every visual detail—he wanted it to feel like a real Western, with no modern twist on it, but with clothes that you would find at a flea market. Which was a bit what I did when I first started at Saint Laurent [going back into the house archives], so we played with the first archive of what I did.

That’s what we did with the other filmmakers as well: We would go through the archives. I’ve been at Saint Laurent for eight years now, and with all the collections I’ve done, there are tons of clothes they can use to create wardrobes. But most of the costuming was custom and specific to the movie and the character.

You went to Cannes with Almodóvar in 2023, and this year you have three films there: Audiard’s Emilia Perez, Cronenberg’s The Shrouds, and Parthenope by Paolo Sorrentino. They are three very different movies and three very different directors, all very deep into their careers. Is it important that the filmmakers you work with are already well-established?

From the start, it was important to think about the prolonged production work, and let’s be honest: It’s a budget, so it is easier to work with people who know how to make a film and have a vision that I love and respect. But I’d like to extend what we do to young directors in the future.

It’s an interesting time: Amazon, or Apple, are some of our biggest producers, and you can look at something like the Met Gala to see how the power of pop culture can respectfully help fund the work of an important cultural institution like the Costume Institute.

Exactly. I mean, [the filmmakers] were a bit nervous at the beginning, but then they understood: It’s not about putting one of our bags in the opening sequence of a film, or talking about the brand during it: I don’t want to see the name of Saint Laurent used in that way, and I will not produce a film about fashion or use a film as an opportunity to make a brand shine.

I’ve noticed that you’ve never launched any product or collections off the back of the movies you’ve produced….

For sure, totally—there’s no Saint Laurent T-shirt in a film.

I know you’re a David Cronenberg fan. From what I have heard of The Shrouds, it sounds like it has his trademark creepiness, yes?

Yeah—it’s strange. It’s very him, it’s very… his films always have that weird technology-meets-the-human-body thing. I like that it’s always the same obsession, but treated differently: You’re never seeing the same thing, but you can see he returns to the same theme.

And what drew you to Sorrentino and Audiard?

Jacques is one of the best independent French filmmakers—I loved Un prophète with Tahar Rahim and De battre mon cœur s'est arrêté with Romain Duris. [His filmmaking is] always very modern and personal. Emilia Perez was very new in its approach and very different from what he has done in the past, but at the same time, when I watch it you can clearly see it’s him. It’s never a cliché.

The same for Paolo Sorrentino. For me, it was like working with a new Fellini. I like the poetry of the script—something that seemed light and easy, but that was just the surface. Something more deep was there between the lines. It’s a very emotional film, probably his most emotional so far.

Is there anyone else you would love to work with?

Of anyone I would love to work with, it’s Martin Scorsese. I met him during an Oscars after-party, and he was super inspiring. For me, he’s a master of the masters—I would love to do something with him. And of course, Francis Ford Coppola.

Lastly, I would love to know: What’s it like seeing your name on the movie credits?

I was emotional when I was sitting next to Pedro at Cannes and saw my name—the graphics on the film are super-bold and super-red, and when I saw his name and then my name, I was like, Shit—wow. When you’re a little kid from Brussels and you see your name in front of everyone at Cannes, it’s emotional. There was a little tear.