Contents

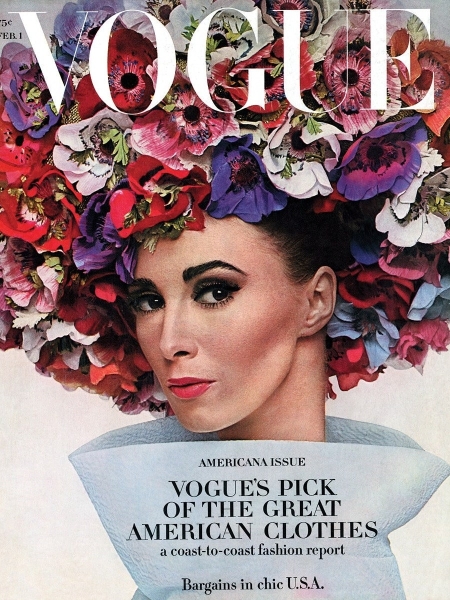

They said the 1960s swung and indeed it did—especially when it comes to fashion. In one corner of ’60s fashion, we had Jackie Kennedy delivering prim and presidential looks in simplistic silhouettes in pastel-pretty colors. In the other corner, we had Mary Quant and her fellow mods who trimmed their hair (into five-point-dos, a la Vidal Sassoon) and raised their hemlines to miniature proportions—the mini skirt was born! In another corner, we had a group so enamored by the space race that they made futuristic shift dresses fit for the cosmos. And, over in counterculture, peace and love were paramount—and folkloric hippie fashions helped a whole generation dress the part. But that’s just skimming the surface of ’60s fashion!

A whirlwind recap of the decade, below.

Women’s Trends of the 1960s: The Mini Skirt Arrives

Honey, We Shrunk the Skirt!

Never before in the history of fashion was the knee on show; you may remember that even the infamous flappers of the 1920s concealed their knees. After the lowering of hemlines in 1947 by Christian Dior, skirts steadily rose over the next decade and a half. Though fashion historians pinpoint 1964 as the year we got the mini, there were precursors—for example, Cristóbal Balenciaga’s sack dress from 1957/58.

So did Mary Quant invent the miniskirt as is often said? It’s not as straightforward as a simple yes. But it was a lace dress from the designer in 1964 and Quant’s accessible price points that really caught on; her lower-cost label dubbed Mary Quant’s Ginger Group really helped fuel the short-skirt craze among the youth. Regardless, it took a couple of years before the style, which first just skimmed the flesh above the knee, was widely adopted. By the end of the decade, it was acceptable for styles to reach micro-mini levels. So much leg was on display that sheer stockings had to be swapped for tights!

“Legs are still it—that's the whole story. And what it boils down to is this: you're going to see a real variety of hemlines now, with nothing but good news for legs,” wrote Vogue in the August 15, 1966 issue.

Youth Is the New Black

The Youthquake Marks the Arrival of Fashion’s New Muse

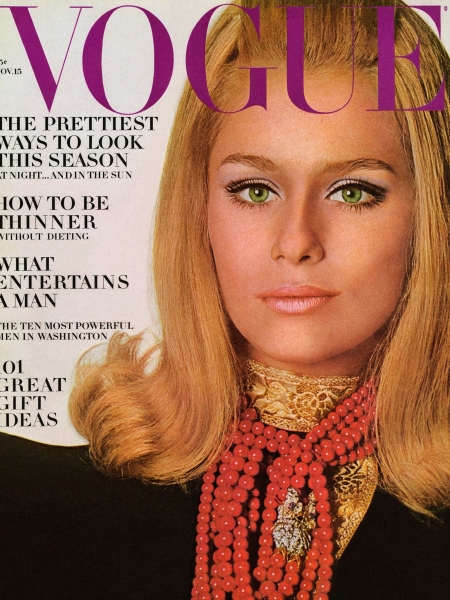

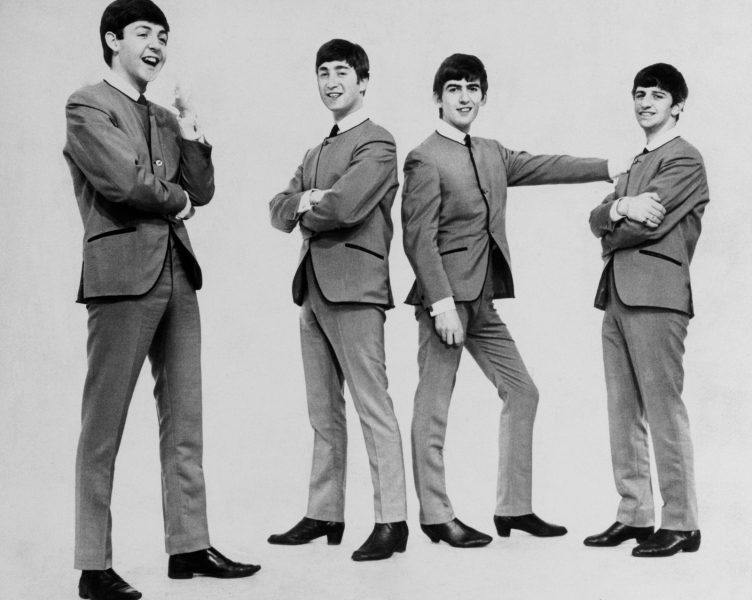

“The year’s in its youth, the youth in its year. Under 24 and over 90,000,000 strong in the U. S. alone. More dreamers. More doers. Here. Now. Youthquake 1965,” wrote Vogue in its January 1, 1965 issue. The term, coined by Diana Vreeland, encapsulated pop culture’s seismic shift—the couture doyenne of the 1950s was no longer fashion’s favorite; she was replaced with a younger, leg-baring woman who listened to rock n’ roll (The Beatles, The Who!) and spent her limited disposable income on disposable clothes designed for the moment. This meant “fast fashion” clothing like paper dresses made from cellulose and hyper-trendy pieces made from synthetic fabrics.

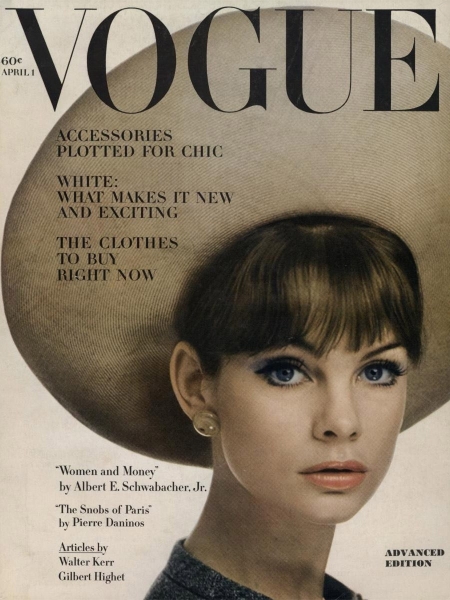

Twiggy, Jean Shrimpton, and Penelope Tree possessed the spirit of the youthquake more than any other model.

Synthetics Proliferate Fashion

New Fibers Are Met With Great Fanfare

In 1960, The Textile Fiber Products Identification Act (“Textile Act”) in the U.S., which required fashion to list its fiber contents as novel fibers, started turning up in ready-to-wear. Perspex, PVC, polyester, acrylic, nylon, rayon, and Spandex were all celebrated as wondrous developments. The biggest adopters of these new textiles were ready-to-wear labels catering to the youth or households looking for wash-and-wear clothing that needed no ironing. It was the dawn of a new era and the moment was marked in an amusing article in Vogue’s April 15, 1965 issue.

“What’s the Hot Ticket? In theatre talk, the one that gets you into the biggest hit in town. The one we’re thinking of has the same aura of success, but a different purpose. … It’s tied or sewed onto every dress made in America, and it tells you exactly what the dress is made of—down to the last fibre. Percentages are given, names spelled out; and some names that used to sound like 1984 or Dr. No's laboratory—names like polyester, acrylic, triacetate—now have a familiar, trusted ring. (We may still not know what they mean, actually, but we know how they perform: brilliantly.)…Some fabrics are all natural fibres, some all synthetic; the great majority are mixtures, with a spectrum of strengths and capabilities.”

The Jackie-Look

A Style Icon in the White House

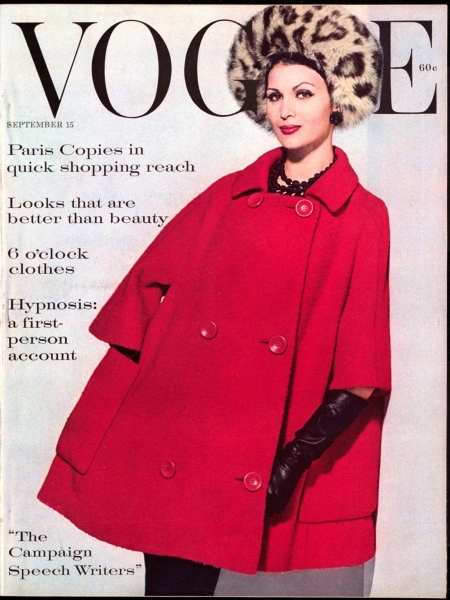

But not everyone wanted to dress for the youthquake. Women who preferred chignons and couture over Vidal Sassoon helmets and inexpensive ready-to-wear had their own muse: Mrs. Jackie Kenndey. If miniskirts and mary-janes were for the sub-culture, Kennedy was the culture. Many Parisian couture houses, like Balmain, Balenciaga, and newcomer Hubert de Givenchy, were putting out prim looks in boxy but tailored silhouettes. The codes developed during Couture’s Golden Age (1947-1957) were attempted in more streamlined looks but with no less craftsmanship.

Skirt sets, trapeze silhouettes, and an overall primness were championed by designers like Patou, Saint Laurent, Pierre Cardin, and stateside by Norman Norell, Oscar de la Renta for Elizabeth Arden, Chez Ninon, and Oleg Cassini. The latter was appointed Kennedy’s personal designer.

A Pret-a-Porter and Retail Disruption

Fashion Gets Democratic

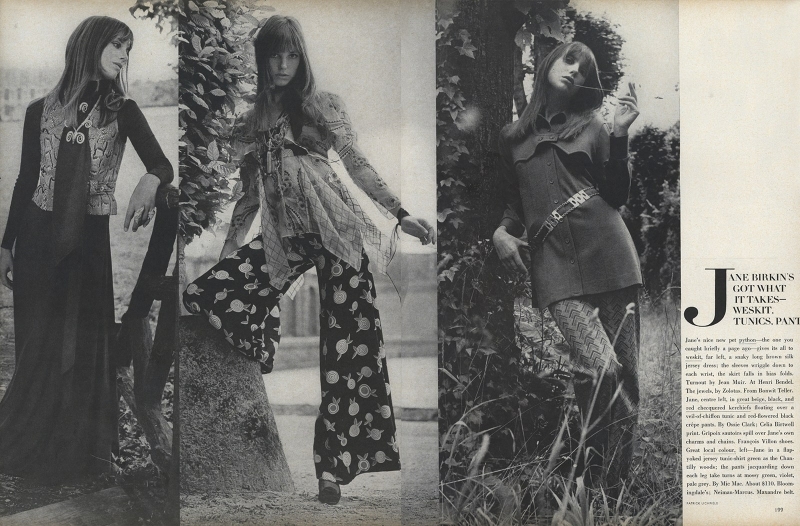

With the Youthquake came a disruption in the fashion system. More and more designers got on the pret-a-porter train with diffusion labels offered at lower price points. By 1959, Ungaro had licensed his name to a ready-to-wear line and Mary Quant launched her Ginger Group line in 1963. Other designer RTW labels included Jean Muir and John Bates.

Retail-wise, if before, shoppers had a choice between department stores and high couture salons, now RTW designers were front-facing and welcomed shoppers in their singular worlds; a new crop of boutiques across London, New York, and Paris served as HQs for the youth culture. Biba, and its art nouveau-inspired interiors on Abingdon Road in Kensington lured the London Mods. Carnaby Street soon contained a handful of menswear shops offering novel takes on the category compared to Savile Row. Over in New York, Betsy Johnson enlivened the Madison Avenue boutique Paraphernalia with low-cost, high-personality pieces modeled by Edie Sedgwick.

Over in Paris, On September 19, 1966, Yves Saint Laurent opened a ready-to-wear boutique called “Saint Laurent Rive Gauche” and in doing so, became the first couturier with his own majorly successful ready-to-wear line in France.

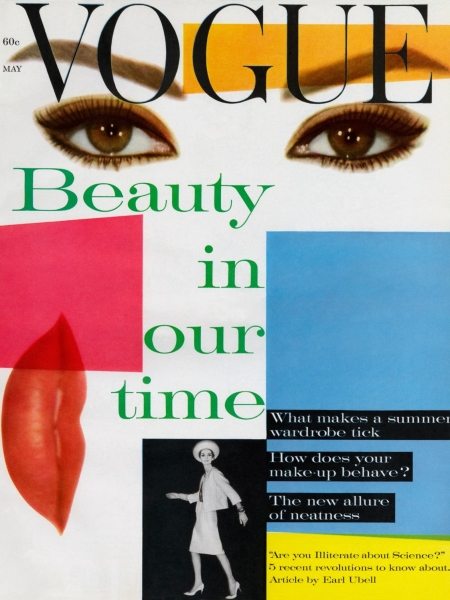

1960s Beauty Trends

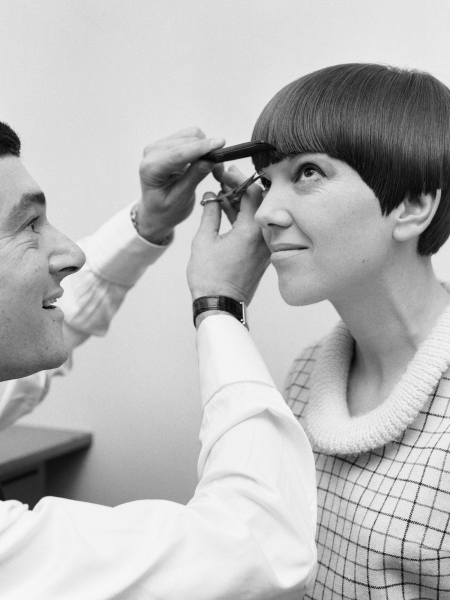

Vidal Sassoon and Bigger-the-Better Eyes

Vidal Sassoon and Bigger-the-Better Eyes As far as beauty goes: the mod look meant short, helmet-like hair—Vidal Sassoon’s asymmetric five-point cut for model Peggy Moffit made waves and so did his cut for Chinese-American actress Nancy Kwan.

“We love the cut Nancy Kwan's just been given by Vidal Sassoon of London. One of the masters of the new school of hair—thought ("hair should comb, should move”), this brilliant young hairdresser has a system—and he’ll tell anyone who asks,” Vogue wrote in its October 15, 1963 issue.

Mary Quant sported the look as did Mia Farrow whose pixie was courtesy of Sassoon as well. If not cropped like a bowl, women wore youthful bangs—see Jean Shrimpton—with lots of volume and a flip like a ski slope and the ends.

The cosmetics industry boomed at the time and technology made for mass production of shadows, mascaras, and lipsticks. The eyes became the focal point with softer lipstick hues for greater contrast of lashes and kohl-rimmed eyes.

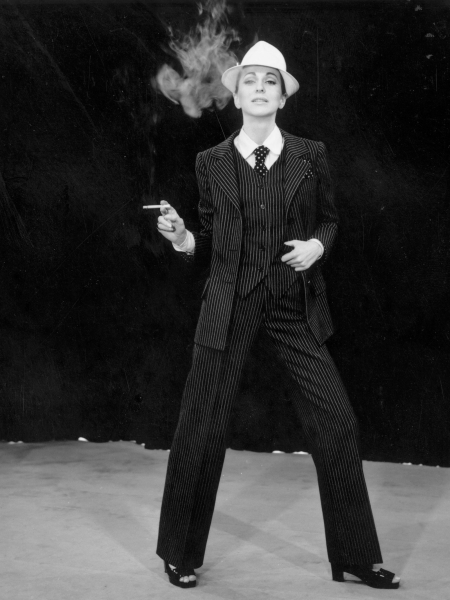

All Hail Saint Laurent

The Designer Gives us Le Smoking and More

If the decade belonged to one designer, it was, without a doubt, Yves Saint Laurent. Though his final collection for Dior in 1960 led to his dismissal from the house (Saint Laurent was also drafted into the army for the Algerian War), it was hugely impactful and simply ahead of its time. Nicknamed the Beatnik collection, Saint Laurent looked to the bohemian Left Pank of Paris for inspiration, riffing on biker jackets and artful tunics in a couture construction—essentially, he anticipated culture’s influence on fashion, having the foresight to recognize the Chambre Syndicale de la Haute Couture wasn’t impervious to outsight sources of inspiration. By 1962, and backed by Pierre Bergé, Saint Laurent was showing his first collection under his own name.

In a few short years, Saint Laurent would give the world icons of fashion—a word often employed but rarely accurate. First came his primary-colored shift dresses inspired by the geometric work of Piet Mondrian in 1965; Saint Laurent, not one of Swinging London’s designers, seemed to beat them at their own game in doing so. In 1966 came the gender-bending Le Smoking tuxedos for women. And in 1967, he delivered his safari-inspired collection, brilliantly documented with a memorable Richard Avedon snap of Veruschka. And Saint Laurent was only getting started.

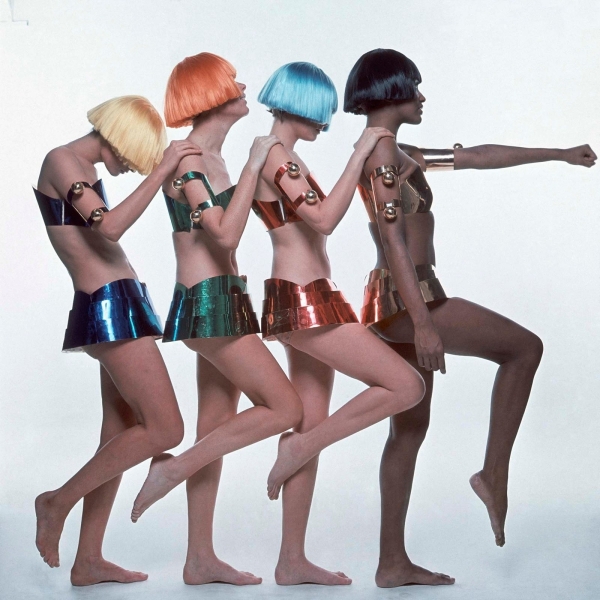

Enter: Space Age

The Future Was Now

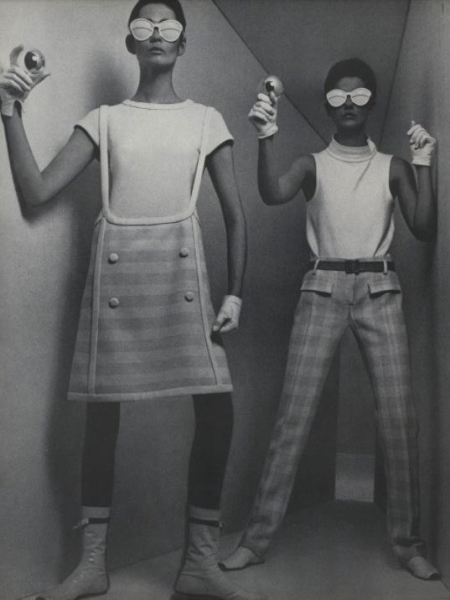

Though the United States went to the moon in 1969, it was years before that that space age fashions were launched. The era’s fascination with space exploration was expressed in a new style movement called Atomic and, in the fashion world, a crop of designers let their fancies take flight: André Courrèges, Paco Rabanne, and Pierre Cardin. Gleaming aluminum foil-esque silver vinyl decorated a collection of PVC moon girl fashions for “Courrèges’ Spring/Summer 1964 ‘Space Age’ collection, which also featured ‘astronaut’ hats and goggles and mid-calf-length boots”. In 1966, Cardin released a collection of pinafore dresses that were worn over slinky knots and turtlenecks.

Enter Hippie Culture

Boho fashion takes hold

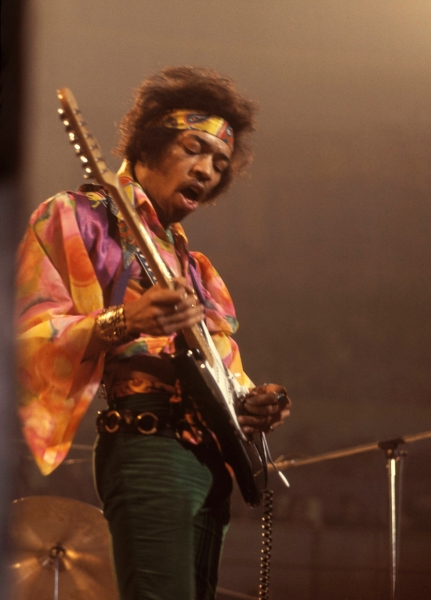

By the very end of the decade, heightened disapproval of the War in Vietnam and a call for civil rights birthed a movement rooted in peace and love. On college campuses, students were protesting the war. In Alabama, a series of three marches, the Selma Marches, in 1965 protested the blocking of Black Americans' right to vote. In 1967, thousands of hippies converged in San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury district to commingle with the like-minded in what’s since been dubbed the Summer of Love. And in 1969, in upstate New York, the unprecedented multi-day Woodstock concert unfolded. Fashion meant bohemian maxi dresses in ditsy florals, loose and billowing silhouettes, and folkloric fashions with Eastern European ties.

The aesthetic was certainly considered a fashion for the sub-culture—though by the mid-1970s, emblems of the look turned up on runways.

Top Designers of the 1960s

Yves Saint Laurent, Balenciaga, André Courrèges, Paco Rabanne, Mary Quant, Barbara Hulanicki, Roberto Capucci,Pierre Balmain, Oleg Cassini, Rudi Gernreich, Norman Norrell, Nettie Rosenstein, Vera Maxwell, Hubert de Givenchy, Emilio Pucci, Claire McCardell, Bonnie Cashin, Pauline Trigère, Hardy Amies, Norman Hartnell, Pierre Cardin

Men’s Trends of the 1960s

Never before did men have more fun with fashion than in the 1960s. For all of the 20th century, men could opt for a suit or something more casual if engaged in sport or leisure. Color, whimsy, and individuality weren’t prized in the sober yet distinguished menswear. At the beginning of the decade, films capturing la dolce vita and the slick-dressed signore in slim suiting (think Marcello Mastroianni) offered a more easygoing way of dressing. Soon men had more options: they could be a mod (short for modernists) and dress in turtlenecks, checked pants, and collarless outwear offered by Pierre Cardin after he trekked to India and fell for the Nehru jacket. Carnaby Street was buzzing and preferred by younger shoppers who wanted to askew the traditions of Savile Row. As the decade hurled forward and musicians like The Beatles, The Who, The Rolling Stones, and Jimmy Hendrix became increasingly bohemian, their fashion reflected the times.

In the Culture

The decade began with an idealistic Camelot Era and, my, how things can change in 10 years! John F. Kennedy was assassinated in November of 1963 in Texas and five years later, his brother Robert F. Kennedy was assassinated in Los Angeles. Earlier in 1962, Marilyn Monroe tragically passed away and in 1969 came the brutal Tate–LaBianca murders from the Manson Family.

Alongside all these dark spots were bursts of optimism, creativity, ingenuity, and technology. Contraceptives for women were available for the very first time; on August 1963, more than a quarter million people participated in the historic March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. People wanted change and they felt they could affect it by banding together. All this while, there was plenty of entertainment to go around from music from The Beatles to Hollywood (The Sound of Music! West Side Story! My Fair Lady!). On the big screen, Frederico Fellini was giving up a mambo Italiano of film, and Hitchcock gave us Psycho and The Birds. And artists like Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein helped us redefine (again) what we considered to be art.