We may earn a commission if you buy something from any affiliate links on our site.

Over the last nine months, Gen Z trend forecaster Casey Lewis started to notice a centuries-old impulse surging on social media. Not for the first time, people were planting an American flag on new territories—in this case, to be specific, Lewis’s TikTok feed. Perhaps you’ve seen them too: There is the Polo Ralph Lauren flag pullover, retailing for just under $400 (a cashmere version costs $1,490), and a Brandy Melville quasi-roll-neck iteration. Tuckernuck produced a take on Americana that cost $248. Denimist sells one for $365. Fast-fashion options abound. Lewis has seen interest grow in a TikTok Shop dupe that costs $11. Creators started comparing their virtues; over Christmas, scores of them unboxed the ones they’d been gifted.

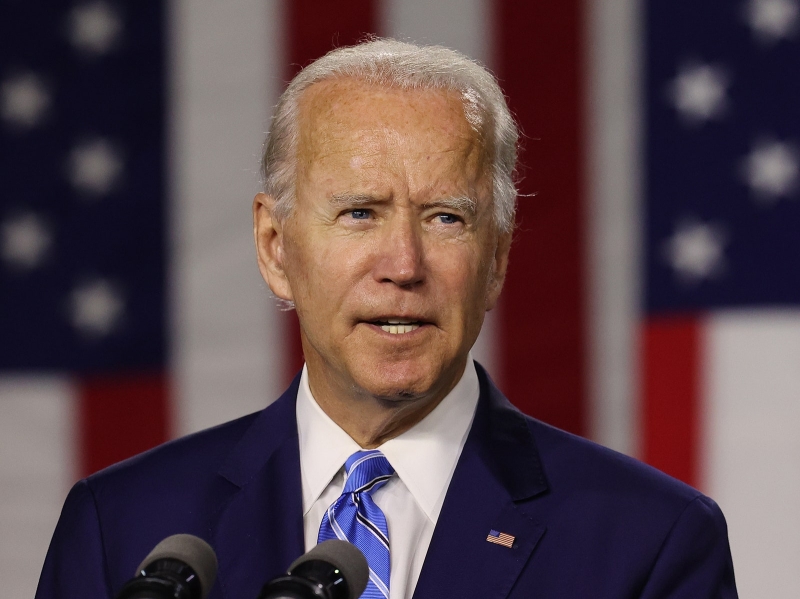

Amid the proliferation—and especially this week, as President Joe Biden and most congressional representatives will likely pin a small enamel version to their lapels at the State of the Union address—a question remains: Can you (not a politician) wear American flag paraphernalia unironically? Can a sweater or a dress declare that America—or at least Americana—can be kind of great, without risking association with the rabid MAGA hordes?

Once the domain of BBQ kitsch and limited-edition Old Navy merch, American flag fashion has taken on a certain charge in the post-2016 era. What’s trending as nostalgia-tinged Americana on TikTok inspires less enthusiastic engagement in deep-blue enclaves. For progressive-minded voters, visual patriotism has been consigned to the dustbin of if not history then at least the one holding all our old skinny jeans and side parts.

The American flag? She’s basic.

The writer Lauren Sherman—the brain behind Puck’s Line Sheet newsletter—grew up around flag tees and Stars and Stripes bumper stickers. To her, the flag was an emblem claimed by the union-affiliated working class. “It just meant that you were proud to be an American, whereas if you wear an American flag now, it somehow indicates that you’re conservative,” she says. She has seen her own family register the shift. When she was a kid, everyone dressed up in American flag tees for July Fourth, she says. “I would say 85% of the people in my family would not wear one now.”

As with any style that falls out of favor, it’s not the flag that has changed. It’s the connotation that has.

In Democratic-leaning cities and towns, where fashion is a more self-conscious mode of social expression, “the idea of patriotism is correlated with isolationists and populists,” Sherman says. Like the flag waving on the front porch, flag hats and pins (except on politicians, for whom it’s a de facto uniform) are seen as accessories for them, not us. That unease has reverberations. Sherman tracks it in the care with which brands incorporate preppiness into their collections; often, it’s prep with a twist or a certain irony, lest it be perceived as old-school exclusionary. Sherman is tuned into the same Polo Ralph Lauren resurgence that Lewis is watching play out on social media, but the most popular looks are “all drawn from vintage Polo,” Sherman points out. The homage is more on-target than its wearers realize. The brand may have been adopted as the uniform of the Mayflower set, but Ralph Lauren himself was born to immigrant parents in the Bronx. Who better to market the flag than a first-generation master of reinvention?

The hesitancy to embrace the Stars and Stripes stands in stark contrast to attitudes around camouflage print, which was, of course, developed for the military and has since turned into a ubiquitous neutral. No one wearing an oversized Marc Jacobs camo print worries that their jacket betrays a hawkish foreign-policy agenda.

To deal with the sartorial ambivalence, Lewis has noticed, some creators wink at a new sweater’s political implication, tapping out captions implying patriotism in a Lana Del Rey way, not a MAGA way, referencing the kind of Americana on display in the singer’s nostalgia-coded music videos. But Lewis thinks most Gen Z’ers who’ve powered the trend don’t see the sweater as a partisan statement at all. “I think it’s appealing to a young generation who has spent a lot of their middle school and early high school years wearing Shein or H&M,” she says. “There’s something about an oversized American flag knit that feels old money.”

Especially for a cohort that hasn’t lived through as many political cycles as its elders have. “The vast majority of TikTokers who share these sweaters are Gen Z,” Lewis says. “I haven’t seen a single millennial TikToker share it or wear it. Millennials have just been through more. They know that things are more fraught. I don’t think Gen Z is wildly conservative. I think they’re sort of unaware of what the American flag represents. It’s not just cute Brandy Melville. It’s more than that.”

The American flag wasn’t always the aesthetic domain of conservatives. In an eerie coincidence, the designer Catherine Maladrino produced a flag shirtdress just before 9/11 that Halle Berry, Julia Roberts, Sharon Stone, and Madonna would all go on to wear. It was semi-sheer, but the pattern was no subtle nod. The stripes were several inches wide. The stars were the size of silver dollars. It was the ultimate statement dress and so popular that Malandrino relaunched it to celebrate the historic election of Barack Obama in 2008. Soon after, Kelly Ripa wore it. Then Meryl Streep did. At the Democratic Convention in 2016, Streep broke the dress back out to deliver her speech to mark the nomination of Hillary Clinton, the first woman ever to top a major party’s ticket. The dress spoke to a conviction: This is the kind of country we can be.

“That just wouldn’t fly now,” Sherman says. A designer touting feminist and progressive ideals “would never make that.” Earnest TikTokers perhaps do not know that the most prominent wearer of the Polo Ralph Lauren sweater in recent months is, in fact, former GOP presidential hopeful Nikki Haley, who has sported two versions. (Meanwhile, Donald Trump has debuted—and sold out—gilded Never Surrender High-Tops, which cost $399 and feature an American flag detail on the back. It’s possible the profits will help offset his mounting legal debt, which, at present, totals well over $400 million.)

The people who wear their patriotism on their literal sleeves tend to be the kind of people who believe the country is moving in the right direction, Sherman says. You’re not going to wrap yourself in the flag if you believe America is careening off the edge.

But there is a subversive way to wear the flag. In 2019, the designer Telfar Clemens welcomed a thousand people to his Fashion Week presentation. The entrance for all of them was a hole ripped in the middle of a giant American flag. In 2021, Zac Posen dressed Debbie Harry in a tattered flag gown for the Met Gala, the dress’s stripes wrapped around a visible cage skirt. Twice now, the label Vaquera has shown star-spangled dresses. In 2017 it produced a saturated, triumphant number with an endless train. The gown had been designed before Donald Trump’s election and shown in defiance after it. In 2022 its collection featured another flag dress. This one was ripped and faded but unmistakable. It was no pristine, preppy sweater, but it sent a message all the same.

Decades ago, punks and rebels in England seized the Union Jack and turned it into a symbol of revolution. “They coopted it,” Sherman says. “And so when I think of the British flag, I still think of the Sex Pistols and Vivienne Westwood”—not Tories and Conservatives.

After November, an American flag print might feel even more verboten than it does now. Or it could take on an iconoclastic kind of significance. “Young people can make it their own,” Sherman says. There’s hope for the old girl yet.